Today, David Cameron is going to make the argument that austerity (or cuts or, as he recently tried to call it, “efficiency”) is an essential prerequisite to growth. This is because the Coalition thinks it is “winning the argument on deficit reduction, but losing the argument on growth”. (These are Nick Robinson’s words, but they sound to me like they’ve come straight out of Downing Street.) The phrasing is of course disingenuous, because it seeks to separate the responsibility for the flatlining economy from the policy – and rhetoric – on the deficit. They are bound up. They cannot be separated.

Labour will argue that no matter how hard the Coalition seeks to shirk responsibility, this recession has been Made In Downing Street, and the public knows it is true.

But is it also true that you can reduce the deficit at the same time as enjoying growth? Of course it is. They must go hand in hand. But here’s what cannot happen: you can’t expect cuts or austerity or efficiency to PRODUCE growth. You must have a strategy for growth which goes beyond “straining every sinew.” (There are debates to be had about shrinking the state in order to “allow” the private sector to flourish. They’re rubbish arguments at the best of times, and in times of recession they are positively dangerous. The results of austerity at home and in Europe are there for all to see.)

And you can’t bang on, as the Coalition has done for reasons of political expediency about the “mess” left by the last government, about how it’s the worst it’s ever been, about the need for drastic cuts across the board, without people eventually hearing you. They will hear you and they will be expecting redundancies and they will be expecting their benefits to be cut and they will be expecting their wages to fall back and they will be expecting their savings to shrink and they will be bracing themselves against the dire storm ahead. It will be a wet winter, a snowy Christmas, the wrong leaves on the line… messing up not just this quarter or that, but messing up the picture for years. Nobody in their right mind will spend, and no business in its right mind will invest. You do not need to be an economist to understand this story. In fact I sometimes wonder if it helps not to be an economist.

But the politics, if not the economics, are easy to see. The Coalition’s very existence depends on its self-proclaimed formation “in the national interest”, in a time of crisis, to fix the economic mess. It simply has to talk about how dirty our house is, in case we start to wonder how much we need the cleaner. Whereas, in the past, chancellors and prime ministers have benefitted from talking the economy up, this government has wrapped its identity around economic despair. It has committed itself to talking the economy down. That’s why it is “losing the argument on growth”. It cannot make an argument for growth at all. It is a problem entirely of its own, cynical making.

There’s a strange idea going round at the moment – eg on Newsnight last night – to the effect that there has been no austerity yet (and, by implication, the Coalition needs to be more brutal). It’s true that the planned cuts have only kicked in by, perhaps, 10%. But that misses the point. Everybody knows deep cuts are in the system, and it is that knowledge, that expectation – constantly justified and reinforced by rhetoric of dire portent – which has already generated the reaction to austerity. That reaction is stagnation and fear, and it has been entirely produced by the merchants of doom in Downing Street.

We used to take “the football boat” from Ryde, and when Anthony’s fortunes improved, he would buy us ‘posh’ tickets in the middle of the South Stand. (Anybody who has been to Fortress Fratton will know that the word ‘posh’ can only be applied in the loosest sense, but that is very much part of its charm.) When Anthony died, my sister and I toyed with the idea of keeping his season ticket going, leaving his seat symbolically empty. Pompey is part of our story: our history, and, hopefully, our future. We’ll see.

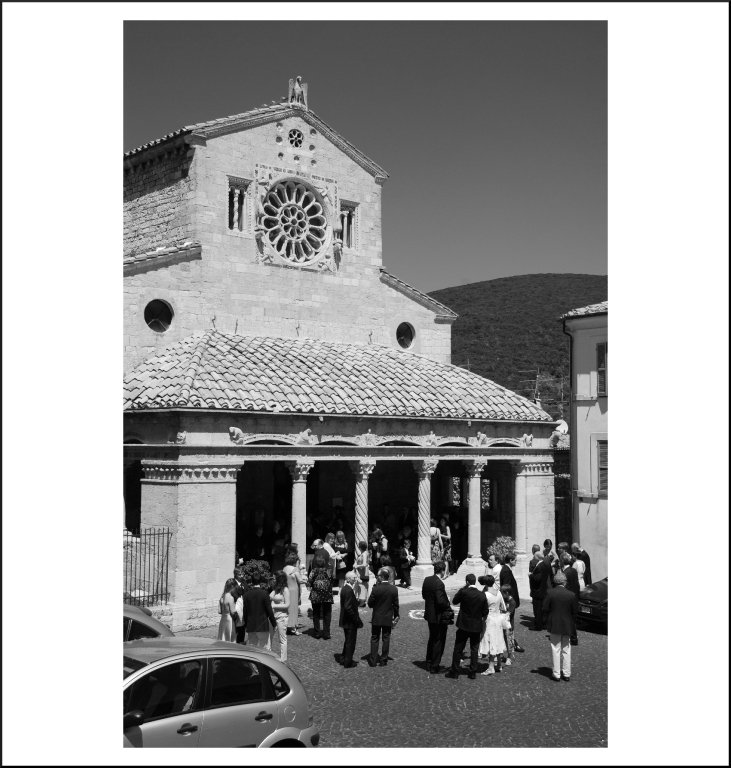

We used to take “the football boat” from Ryde, and when Anthony’s fortunes improved, he would buy us ‘posh’ tickets in the middle of the South Stand. (Anybody who has been to Fortress Fratton will know that the word ‘posh’ can only be applied in the loosest sense, but that is very much part of its charm.) When Anthony died, my sister and I toyed with the idea of keeping his season ticket going, leaving his seat symbolically empty. Pompey is part of our story: our history, and, hopefully, our future. We’ll see. In recent times, I have taken to spending a part of my year in Umbria, Italy, just north of Rome. There is no family connection there, just a love of the place. I have found an increasing sense of belonging in a wonderful hilltop town on our doorstep called Lugnano in Teverina. When I recently went to report a burglary to the police there, the carabiniere made me describe everything to him in painstaking detail, enjoying my comic struggle with Italian, before revealing that he knew everything already: word gets round in a town that small. You either love that kind of thing or you hate it, and I love it. It’s a totally brilliant community.

In recent times, I have taken to spending a part of my year in Umbria, Italy, just north of Rome. There is no family connection there, just a love of the place. I have found an increasing sense of belonging in a wonderful hilltop town on our doorstep called Lugnano in Teverina. When I recently went to report a burglary to the police there, the carabiniere made me describe everything to him in painstaking detail, enjoying my comic struggle with Italian, before revealing that he knew everything already: word gets round in a town that small. You either love that kind of thing or you hate it, and I love it. It’s a totally brilliant community. Finally, I adore red wine. I know next to nothing about white. But a wine dealer friend, the excellent Sebastian Peake, forced a case of a particular white on me a few years back. It’s a vermentino and it is a revelation, a small shipment from heaven. I associate it with a physical release of tension – that tightness in the pit of the stomach that tough days can induce dissolves with the first glug of this particular cool, minerally (but smooth) wine. Actually ‘dissolves’ isn’t the word. The tension snaps away before the wine even hits the back of the throat, in what can only be a pavlovian response to its aroma.

Finally, I adore red wine. I know next to nothing about white. But a wine dealer friend, the excellent Sebastian Peake, forced a case of a particular white on me a few years back. It’s a vermentino and it is a revelation, a small shipment from heaven. I associate it with a physical release of tension – that tightness in the pit of the stomach that tough days can induce dissolves with the first glug of this particular cool, minerally (but smooth) wine. Actually ‘dissolves’ isn’t the word. The tension snaps away before the wine even hits the back of the throat, in what can only be a pavlovian response to its aroma.