Need a cheer up? Here’s our Louisa “live” from her rooftop in North London.

Need a cheer up? Here’s our Louisa “live” from her rooftop in North London.

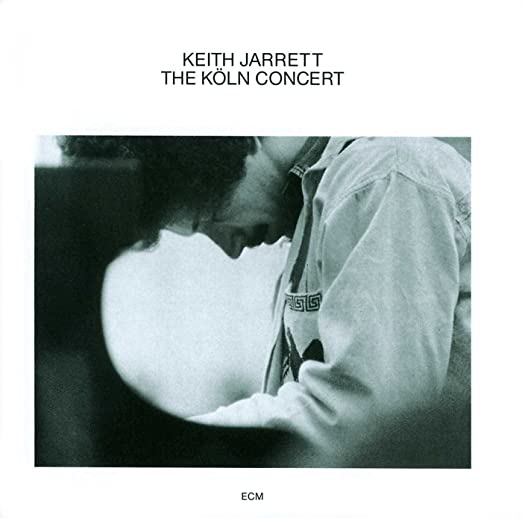

Imagine sitting down at the piano and playing the fucking Köln Concert.

Imagine that. Sitting down and giving birth to that thing.

I don’t care how much prep he might have put into it.

To sit down and unload that astonishing, profound, everlasting piece of virtuosity onto an unsuspecting world. It beggars belief.

Its pounding, percussive rhythms, its soaring melodies, its incalculable, seemingly-careless complexities enter into the listener’s very being. For Those Who Know, Köln is a part of them, a part of life.

As solid and defining as the memories of youth. For me it is as vital and essential as the curve of Appley Bay; the aquamarine of the Solent; the wet planks of Ryde Pier; the heady brine of summer; the sound of the SRN-6 hover whining onto its concrete platform; the sight of Mum at the Mayfayre’s Falcon stove; Muriel at the counter; Jean at the baking table; the arid paper-smoke smell of the Commodore’s bins; Vernon the projectionist’s terrifying oxygen bottle; the sound (and the dread) of Dad firing up The Machine; the endless labels and lids; the cream machine; the dusty box of mechanical Happy Wanderer devices which never made it into the ice cream vans; the unsettling Lonely Man Beside A Train Tunnel I thought I saw on the tiles round the bath; riding no-hands with Daz, as we could do, for literally miles; practising our skids on the ice patches of Spencer Road; the anticipation of Ant coming home; my sisters singing So Far Away; the sound of Dad’s keys hitting the sideboard when he got back late from the election count – softer if he’d lost, or with a discernible splash if he was home in triumph.

The Köln Concert sits alongside all of those deeply personal flavours and tastes. But more than that, it facilitates them. It frees the mind and opens it to the heart. It catalyses and romanticises and celebrates. It deepens sadness, it fuels joy, it puts thrust into lust and – most of all – it soars. It convinces you you could fly.

And if you could fly, this would be your soundtrack.

It is that extraordinary.

And a man sat down and made it. Sure, he probably plotted his ideas. Part IIc is so exquisitely well-formed it must have been pre-configured. But the Concert’s opening, a nod to the bells of Köln and that particular audience, seems to have found itself, to have unearthed itself as the pianist patiently, delicately dug into the theme those three bell-notes suggested. It was archaeology with imperfect tools, too – the piano had some problems, but there was no time to replace it, so Jarrett had to make do and play round its issues.

Keith Jarrett sat at a piano on 24th January, 1975, and he made this.

In March, 2020, when I thought my number was up in hospital, this was my number; I played it as loudly as my phone and my nurses would permit. Köln Concert as Covid commiseration.

What am I trying to say? I suppose it’s just awe, plain and pure. Awe at this unsurpassed and mostly-spontaneous expression of genius. And what it tells us about who we are. Who we can be. I write this as a virus terrorises all humanity, America burns with race riots, and politics in the UK, the US, China, Russia and much of Europe have patently failed us. There seem to be few reasons to be cheerful.

But, God, the Köln Concert restores your faith, lifts your soul, replenishes and astounds. When my friend, the artist Gregor Cürten, casually mentioned at a recent dinner that he was there in the audience at that concert, I was nearly sick with envy. In fact, for a few undignified seconds, I hated him, like a spurned husband. Because if I could attend any one creative event, this would be it. Keep your Mozart. And I’ll marvel at Bach as much as the next man. But this one, extraordinary moment – in a career littered with extraordinary moments – is not just piano, and not just music. It is mankind at its most transcendent.

Louisa Minghella (aged 15) guesting at the Pizza Express Jazz Club Soho, some moons ago. Caught on camera by the iphone-ready hero, Kirk Jones.

(Stage courtesy of Edana Minghella and friends; song courtesy of the LGBT community.)