In the mid-90s I set fire to myself. My sister and her husband arrived for dinner from the Isle of Wight. I turned up the gas on the stove and threw the pasta into the boiling water.

As they came in I turned to greet them. The kitchen in our little flat was tiny. I leaned back and saw their faces turn from glad-to-be-here to sheer horror. Then I felt the flames at my back. My shirt was on fire.

I’ll spare you the details but I was extensively burnt. At Hammersmith A&E I waited many hours with no treatment for a doctor to examine me, just a protective pad over my back.

As I waited in pain I consoled myself that I was faring better than the previous occupant of my cubicle: it was spattered with blood, in an impressive, murder-scene arc.

Eventually an exhausted young doctor examined me. She was so tired that she did not lift the pad, but saw some exposed burns near it, and thought them minor. A nurse had to lift the pad and show her the full extent of my burns.

My injuries would have been better if I had not had to wait hours without treatment, but they were not so bad as to require admission. I was cleaned up and bandaged up and told to return daily.

On my next visit, a doctor asked a nurse to clean up my burns. I heard muttering outside and then the doctor exploded. “We’re in a major London A&E – are you telling me we don’t have a disinfectant to clean this patient’s burns?” That WAS what they were telling him.

Eventually the doctor asked for saline and hydrogen peroxide and mixed them and cleaned me up himself. After a few days, I began to feel really fragile. Going by bus to the hospital was really uncomfortable. I boarded slowly and carefully, irritating others.

When the bus jolted and I hit my back, I wanted to cry out. I was exhausted and in pain and remembered feeling: this could be what it feels like to be old in the city and not getting the care you need.

Several days after my accident, I was back again in the A&E cubicles awaiting another dressing change. I realized it was the same cubicle I had lain in for hours on that fateful night. It had the same arced blood spatter on the walls, now old and dried and so very, very grim.

Back on the bus, sitting forward and hanging on tight like an old man, a rage grew inside me and I thought: our NHS is screwed. We have to do something. We cannot just let this happen. I got in touch with my local Labour Party and signed up.

I wasn’t a campaigner back then, but I followed politics with a new keenness. I was in my mid twenties and already feeling vulnerable. I wanted a healthcare system that would see me through, and there was every sign that that was a pipe dream. No disinfectant in A&E, FFS.

John Smith died and I watched the hustings for the new Labour leader. Prescott, Beckett and this young guy, Blair. Blair looked nervous as hell, but spoke with vision and optimism. Three years later, Britain was a different place, with a future ahead of it, a sense of renewal and community.

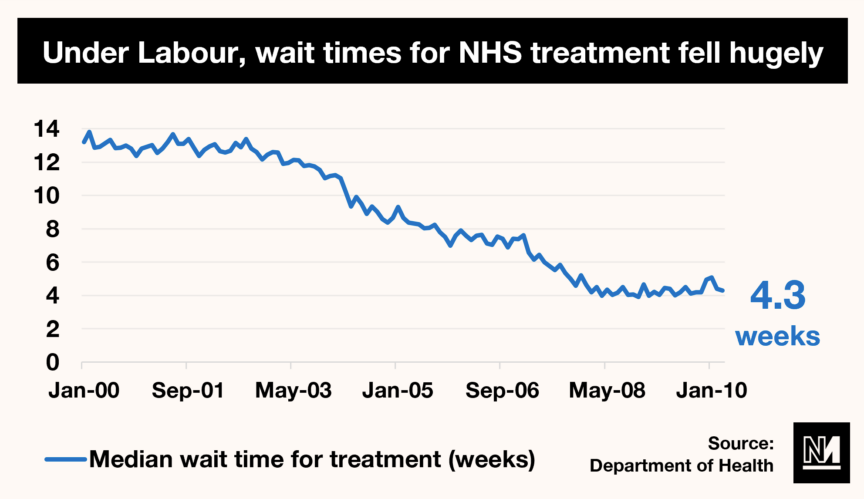

The NHS was rebuilt. A four-hour limit was set on A&E waiting times. Spending was raised to the EU average. Treatment waiting lists steadily shortened. I had started a family and my fear that the health service might, some day, cease to be there for us fell away.

I forgot all about that moment in 1994. The long painful wait in the night. The obviously overworked doctor. The absence of disinfectant. The uncleaned cubicle. Those days were gone. By the end of the Labour government, the NHS was our proudest boast.

The NHS, still, for the 2012 Olympics, was THE thing that united us and even defined us. But it didn’t come to define us by accident. It did so as a result of a Labour government’s steady investment, commitment and reform. It wasn’t perfect, but oh boy, it was better.

And yet here we are again. The NHS is in existential crisis. On Sunday, Royal College of Emergency Medicine president Dr Adrian Boyle said between 300 and 500 people were dying every week as a result of delays to emergency care. Once again, we must hope and push for a decent government to restore it. It will come. It will happen. But meanwhile, many of us will have our confidence tested, and our sense of security stripped away.

Some of us will wait too long in pain for acute or chronic care. Others may pay the ultimate price of bad government. If you are worried, as I was and as I am, do something. Hold on tightly on the bus, get home and join a progressive party. Campaign. Win. And #takebackBritain.